For many people wanting to electrify something in their home - be it a car, water heater, or something else - there remains a burning question: do I do it now, or wait for my appliance to fail?

The simplest way to answer this is by looking at the ratio of new pieces of equipment made in the world, and making sure as many of those are the clean version as possible. I.e., the way to reduce the most CO2 emissions is to buy a new electric car, and sell your old car to someone who would otherwise buy a new ICE vehicle. Not only does this maximize the electric equipment being deployed at home, but dollars spent frequently support new companies developing these products at a time when they need the sales the most.

There are many other nuances to this question, from analyzing the emissions of a particular widget being manufactured, to gauging the cultural influence of someone seeing their peer make new technology choices - and be happy with them. Let's dive in.

Electric Vehicles

Emissions from Manufacturing

Large corporations will typically produce annual sustainability reports. These are intended to be easy for anyone to read. Partially thanks to pressure from ESG investor groups like Parnassuss this is becoming more of a reality. (I'm linking to parnassus because their website has third-party vetting material, including their own impact studies.)

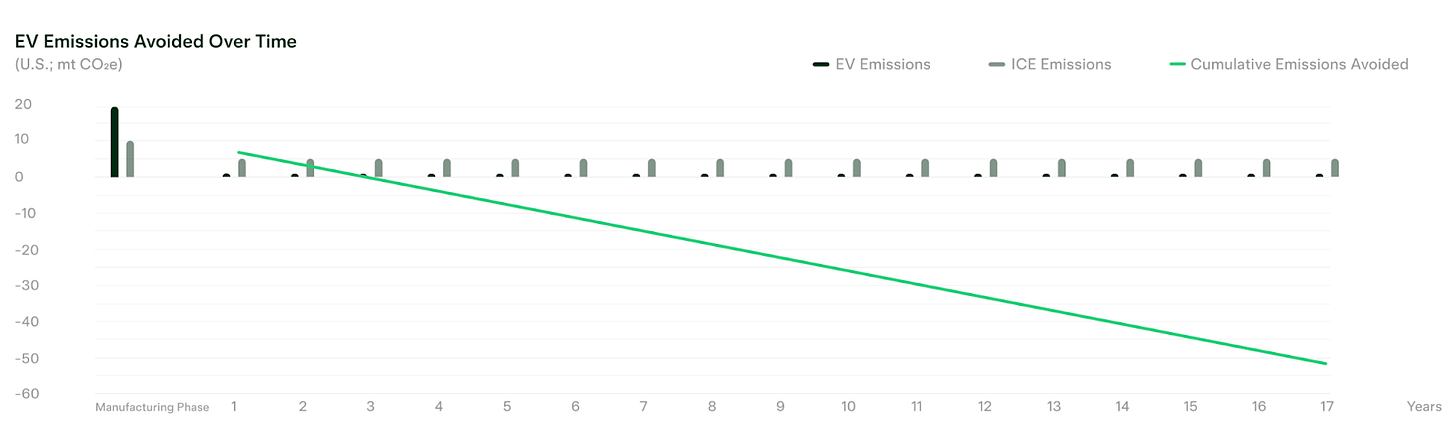

Tesla's annual report shows their cars need to be driven about 13k miles for emissions of manufacture to be net-zero.

This depends on a number of factors, such as where the vehicle was produced and the cleanliness of the grid where it is operated. Bottom line - even if Tesla is padding by a factor of two, vehicles would be likely to be net-zero within two years for most drivers, and then just keep getting better as vehicles are used on increasingly clean grids. When a vehicle reaches its end of life, that battery can be recycled (such as on Currents Marketplace) or used for static grid-storage.

On average, EVs emit roughly a quarter more CO2 during manufacturing than ICE cars, but this quickly pays off even on the dirtiest electric grid, as the images below show. Even mining itself is showing its first hints of electrification– this electric excavator has been operating in Australia since 2023, and has moved more than one million tons of ore.

Global emissions are reduced the fastest if the ratio of new cars sold moves quickly to electric. For someone in the position to do so, buying a new EV and selling a good used ICE car helps EV manufacturers on the one hand, while discouraging the purchase of new gas cars due to a healthy used-car market.

Emissions from Driving

It may be a surprise to hear that even an EV on North America's dirtiest electric grid is still a cleaner choice than operating a vehicle with an internal combustion engine.

We can explore the data with CarbonCounter, a little gem out of MIT. The tool creates a chart of emissions (Y axis) vs cost (X axis) of all sorts of cars, and even lets you see results set to the electric makeup of particular US states.

Even a grid with coal is more efficient than a gas car. This is partially due to the efficiency of industrial-scale generators, which can sometimes get to 50% efficiency compared to the 30% of a gas car, and partially due to the fact that every EV has regenerative braking, letting it charge up when slowing down or going downhills.

Emissions from the Home

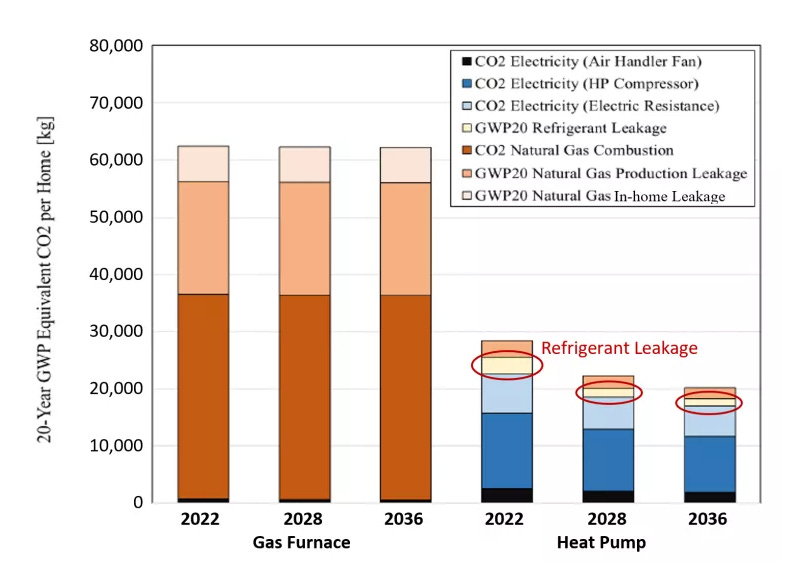

Emissions from heating a home can be notoriously high – for most households, slightly more CO2 is emitted annually from heating than from driving. Modern Heat Pumps are state-of-the-art, as they use electricity to move heat from outdoors to indoors at about 25-35% the cost of the traditional electric-resistance heating briefly popularized in the 70s. For 98% of U.S. houses today, a heat pump will produce less emissions than what is currently installed.

How it works: A heat pump can be thought of as a large sponge, soaking up heat outdoors and "wringing it out" inside. You can learn more on my Homeowner's Guide to Cold Climate Heat Pumps.

Manufacturing emissions of heat pumps is rarely talked about. I suspect this is because they don't have a battery requiring co2-intensive mining. Nonetheless, I took a quick look at Mitsubishi's sustainability report, and confirmed they do have Net-Zero commitments with milestones at 2050, 2030, etc.

A secondary source of emissions occurs if a heat pump leaks high-pressure refrigerant into the atmosphere. Even accounting for this, a heat pump is by far the preferable choice. Also, modern refrigerants, such as R-454B, Propane, and CO2, are working their way to North America, reducing the cost of leakage.

In New England, Heat Pumps + Wood Stoves are a popular combination, in part thanks to the sentimentality of woodstoves and the unreliability of the electric grid. There's a huge range between the CO2 of a tree cut in your own lawn with emission-free tools, and wood trucked in with diesel, or even brought across the Atlantic ocean (shipping wood to England for their "green" bio-fuel has become a recent scandal). Modern woodstoves have secondary burners and catalysts in their exhaust manifold, letting them burn all night, and pushing efficiency up to 80% or more.

Cook-Stoves

Induction and electric stoves may have a longer CO2 payoff period than a heat pump water heater or mini-split at home, as they typically use less fuel annually and don't have the greater-than-100% efficiency which heat pumps have. Still, there's a strong rationale to switch, including well-documented asthma correlations.

Cultural Effects

A single homeowner cannot solve climate change on their own, but they can as part of a movement. That only happens if one follows a piece of entrepreneurial advice I saw years ago: Do Things, tell people.

Any new technology, from heat pumps to green steel smelting, will fall somewhere on the "market penetration" curve below. As we electrify everything, myriads of people are working in every industry to move their particular puzzle piece forward and incrementally more "green". And almost every one (perhaps outside of solar and wind) is in an early adopter phase. And none of them get out of that phase without those early adopters buying in, trying the tech, and telling people.

Right now US steelmaking is in its infancy – it's in the "innovators" phase for green steel. Green steel plants have been being built across the US for years, with billions more in funding being awarded just weeks ago. In a world perfectly optimized for fastest CO2 reduction, this curve for green steel might overlap exactly with that of electric stoves and other manufacturing – but trying to time your purchase to force that is guesswork at best.

US households might be somewhere in the "Early adopters" phase with our electric or induction stove usage. Although the technology is mature, their popularity is more nascent. Reasons for this range from from induction stoves having taken longer to invent and being more costly, to the more adversarial "Operation Attack" in which the American Gas Association, funded by your utility bills, went on the offensive to downplay stove emissions while glorifying the superpowers of cooking on gas (including an infiltration of Julia Child's wonderful TV show).

Contrary to the belief that gas cooktops can't be beat, If you ask a person who owns an induction stove they will probably tell you about how quickly it boils water and how easily it keeps constant heat.

Electric vehicles are in the early majority, with Europe and China leading the way. Back in 2022, 22% of vehicles sold in China were all electric!

The Hard Part - Living with it

Like it or not, the world we live in is built on fossil fuels. It's the unfortunate truth that, as Bill McKibben says, to care about one's own emissions today is an uncomfortable exercise in hypocrisy. There's usually no easy or fun way out. But we can take some solace in the fact that every EV on the road, heat pump installed, or stove electrified brings down our own emissions and that of the fields we work in. If it wasn't for the very first EV drivers, there would not be infrastructure for today's EVs to use. If it wasn't for the first homes with solar, we wouldn't see today's homes with negative power consumption.

Special thanks to Jordan Angerosa for reviewing & contributing to this post